Image: GPSJam.org

What’s New: Analyses from the Univ. of Texas Radio Navigation Lab and Stanford of Russian jamming in the Baltic.

Why It’s Important: Electronic warfare is warfare. Russia is attacking, albeit at a low level:

- The ships and aircraft of other nations while they are in international waters and international airspace.

- The sovereign territory of NATO member countries.

What Else to Know: Most of the ships, aircraft, and infrastructure/applications attacked rely heavily on GPS and other satnav. In some instances they have no alternatives.

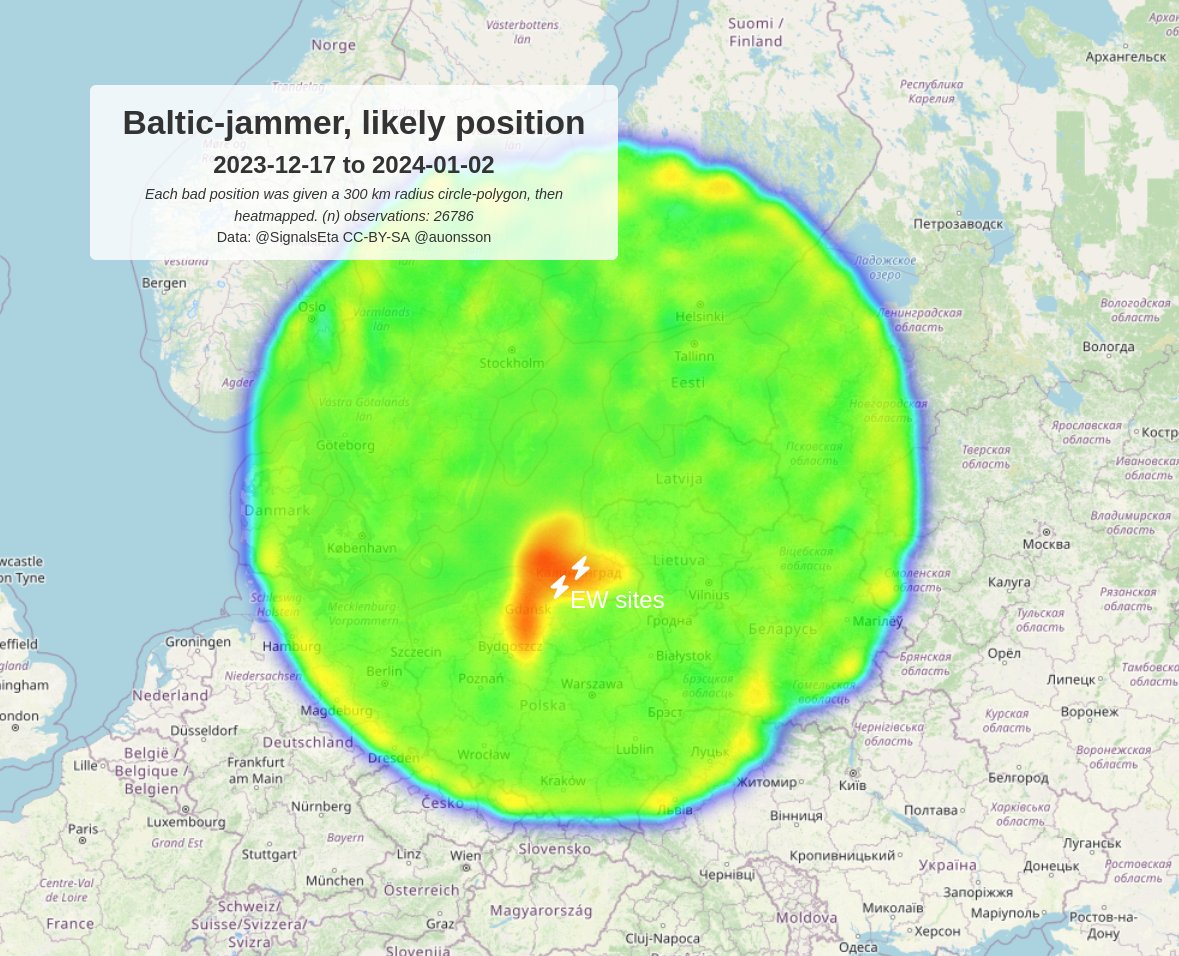

- Since the below article was written one analyst posted on Twitter their conclusion that much of the jamming came from Kaliningrad, Russia:

- We expect there will be further academic analyses of these incidents that we can share at some point.

- The below article was written by the President of the RNT Foundation.

From Russia with love for Christmas: Jamming Baltic GPS

Actions likely in response to U.S. and NATO moves

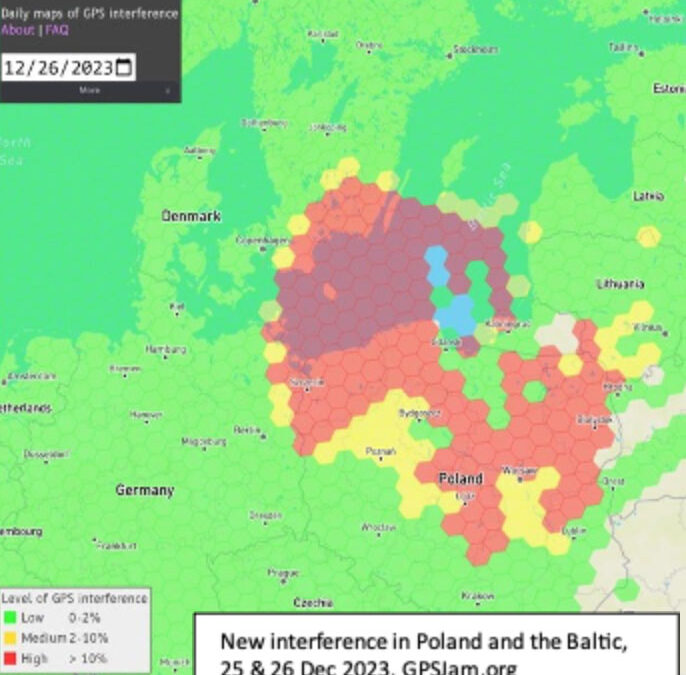

Parts of Poland, Lithuania, southern Sweden, and other countries in the Baltic region had an unexpected Christmas present this year. GPS signals were disrupted and not available in many areas on the 25th and 26th of December. Poland seemed to be particularly impacted, with the northern two-thirds of the country affected and many users on the ground and in the air having to make do without reliable service.

On New Year’s Eve, parts of Finland experienced significant jamming as well. The most visible impacts of the holiday events were seen in aviation and low navigation integrity reports from ADS-B systems. These were displayed on the GPSJam.org website.

Experts in the United States and Poland point to Russia as the source of the interference. They say that Russian anger over the activation of a U.S. anti-missile system in northern Poland in mid-December, and Sweden’s progress toward NATO membership with a recent positive vote in the Turkish Parliament were likely motivations.

Such a reaction by Russia is not unprecedented. In 2022 President Putin threatened Finland and Sweden with invasion if they sought to join NATO. Subsequently, Finnish President Niinistö met with President Biden to discuss improving defense ties. Shortly thereafter planes flying over Kaliningrad and nearby areas in the Baltic began reporting GPS jamming. Analyses of the event by graduate students at the University of Texas Radionavigation Laboratory and Stanford University have provided some details and will likely reveal more as time goes by.

Zach Clements at U.T. studied the disruption and discovered that it included several transmitters spread across a wide area. Some were simply jamming GPS signals to deny service. At least one transmitter was spoofing aircraft so their instruments would show them far from their actual location.

While the phenomenon known as “circle spoofing” has been frequently observed with ships, this was the first time it was reported in aviation. With circle spoofing a receiver is electronically captured and “moved” to a different location. Then it is made to appear to move in circles, almost always in a clockwise direction

Clements is reasonably sure the source of the circle spoofing was inside Russia. “The points at which the aircraft began to be impacted by the spoofing and where they regained authentic GPS indicate that the spoofer is somewhere in Western Russia. Interestingly, the location to which the aircraft were spoofed is a field about a kilometer from Russia’s decommissioned Smolensk military airbase.”

Clements’ previous research has demonstrated how sources of GPS disruption can be located by satellites in low-Earth orbit.

Zixi Liu at Stanford has discovered that the interference was actually two separate events. The first lasted from 9:30 PM on the 24th until 4:30 AM on the 25th, with the second beginning around 2:30 PM on the 25th and tapering off around midnight on the 26th.

Liu’s previous research used aviation ADS-B data to geo-locate sources of GPS disruptions. She is continuing to examine these incidents to see whether the locations of one or more of the jammers can be determined.

Aviation interests have become increasingly concerned about interference with GPS signals since 2019 when a commercial passenger aircraft flying through smoke nearly impacted a mountain. Since then, aviation groups have raised the issue, national authorities have been regularly issuing warnings, and the UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization has urged its member nations to take action to prevent interference.

Intentional jamming and spoofing seem to be getting much more frequent, though, especially in and around conflict areas. In April, Eurocontrol, the European air traffic control organization, warned its members and aircraft using its airspace about these increasing trends.

This fall a spate of aircraft being spoofed in the Middle East, and in at least one instance nearly entering Iranian airspace without clearance, caused particular alarm.

“Aviation is always at greater risk when GPS signals are not available or are compromised in some way,” according to Joe Burns, a senior captain at a major international air carrier. Burns is also a member of a board that advises the U.S. government on GPS and related issues. “Interference with GPS increases the risks of accidents and almost always slows the system down, makes flights longer, and more expensive,” he said.

The International Air Transport Association is meeting this month to discuss GPS interference. Most agree, though, that most meaningful short-term solutions will depend upon the cooperation of national governments across the globe.