Blog Editor’s Note: This is the fourth of four articles Katherine Dunn published last week as part of the Fortune series “When GPS Goes Wrong.”

This article recounts a project by DLR, the German Aerospace Center, to assess maritime GPS disruption in various areas – port, waterway, coastal, and open ocean. Spoiler alert – They found GPS disruption everywhere. Even in the open ocean.

While we have previously reported on this project, the below article has a number of direct quotes from Emilio Pérez Marcos, the lead investigator. We think you will find it of interest.

Emilio spoke about this project at a recent ION conference. Here is a link to Emilio’s ION paper.

The long ocean voyage that helped find the flaws in GPS

This article is part of the Fortune series, “When GPS goes wrong.”

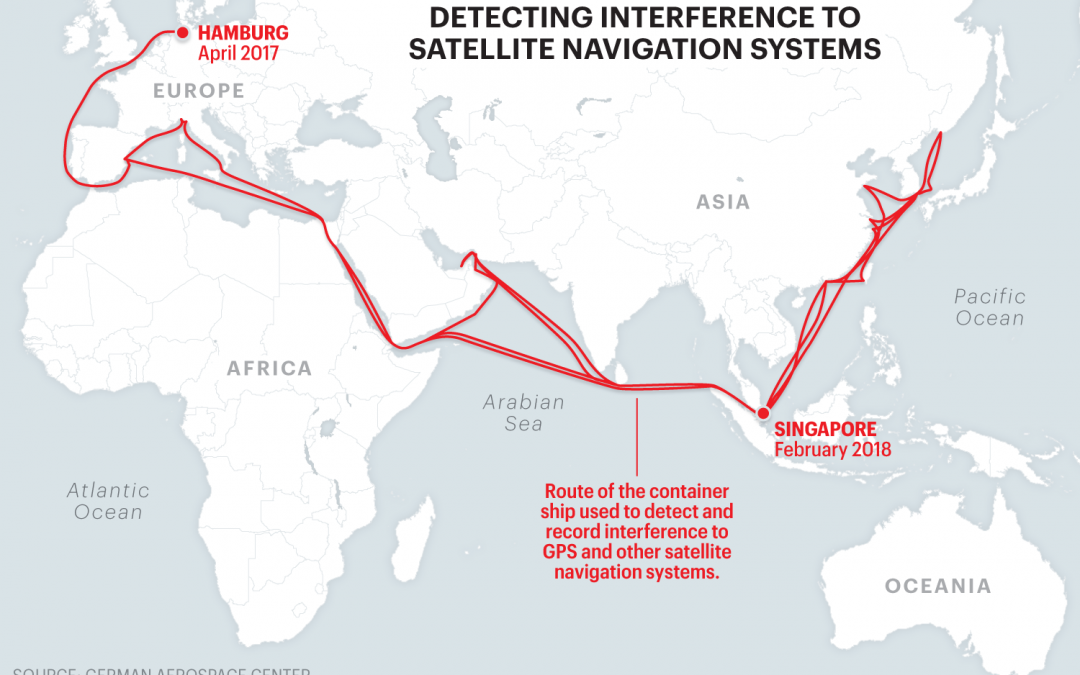

In late April 2017, a commercial container ship left port in Hamburg, Germany. The ship looped around western Europe and through the Mediterranean, then passed through the Suez Canal to the Middle East, on its way to Asia. It was the first of many times the Basle Express would traverse a path between the continents, traveling thousands of miles and heading as far afield as far eastern Russia, before ending its journey in Singapore 10 months later.

The vessel itself was sailing standard commercial seaways. But it carried special cargo: On board were two specially built receivers developed by the German Aerospace Center, Germany’s counterpart to NASA, to detect the frequency of disruption to GPS and other satellite navigation systems along its route.

GPS interference was a problem that, by 2017, was anecdotally on the rise, according to multiple maritime experts and government agencies—and it was beginning to make the shipping industry nervous. (See Fortune’s feature story on the phenomenon here.)

The interference had been linked to “jamming” and “spoofing” techniques, which interrupt genuine satellite signals, either by disrupting them entirely or producing fake signals that can mislead a receiver. Commercially available “jammers”, though illegal, were cheap, and easy to find online, and disruption had increasingly been reported in geopolitical hotspots, particularly in the Black Sea around Russia-annexed Crimea. Later that year, after the Basle Express began its voyage, authorities in Norway and Finland would report outages during NATO drills.